The “compassion” of letting people sleep on the streets is misguided

As this winter’s bitter cold spread over New York City, it presented the first urgent crisis for Zahran Mamdani’s fledgling administration.

Tragically, 18 people died in the deep freeze – At least 15 people directly suffered from hypothermia – which has led to City Council hearings so far through no fault of the mayor.

Despite the dangerous temperatures, Mamdani said people will not be asked to take shelter; He also ordered the NYPD to stop demolishing homeless encampments. Only as a “last resort” can someone be forced to enter.

within Those who died were Frederick Joneswho was found in front of a D’Agostino supermarket at 35th Street and Third Avenue on the morning of January 25.

“He was loved,” his sister, Valerie Atkins of Rosedale, Queens, told The Post. She fondly recalled how the brother she called Freddie had a “gentle soul.”

“It is almost impossible to put into words how many people shared the same story: whenever they saw Freddie, he would often ask them if they needed anything,” echoed their sister Theresa Belcher-Leadbetter.

Jones was beloved. He already had a house, thanks in part to New York taxpayers.

The 67-year-old lived in subsidized housing in the city centre, about a mile from where he died.

“I don’t know why he’s out there,” Shawnell McKinley, the court-appointed conservator, told The Washington Post. “He had a roof over his head. He had an apartment.”

That Jones chose to spend time on the streets — even in the bitter cold, and even when he had a place of his own — highlights how difficult it is to manage homelessness.

By basic scale, Jones could have been viewed as a success story. After living for many years on the streets, where he struggled with alcoholism and mental illness, he was able to find permanent housing in 2017 in Times Square, a supportive housing building run by the nonprofit Breaking Ground.

Jones’ apartment is an SRO — one of more than 5,000 units, McKinley said Break the ground Runs – It was small but adequate. He had a private bathroom and shared a kitchen with other tenants.

The West 43rd Street residence has on-site social services, including psychological and medical services, which he reportedly used.

But that social safety net wasn’t enough to keep him safe and indoors, leaving many questions about the Mamdani administration’s response to Arctic temperatures when Winter Storm Fern hit the city.

The city’s 311 and 911 systems received a total of three calls about Jones in the hours before his death. Gothamist reported. According to an NYPD spokesperson, he waved to emergency responders when they first arrived. The second time, they were unable to locate him on the street.

The latter came the next morning from D’Agostino’s workers who found Jones sprawled out in the snow with a bottle of liquor beside him.

It’s too late.

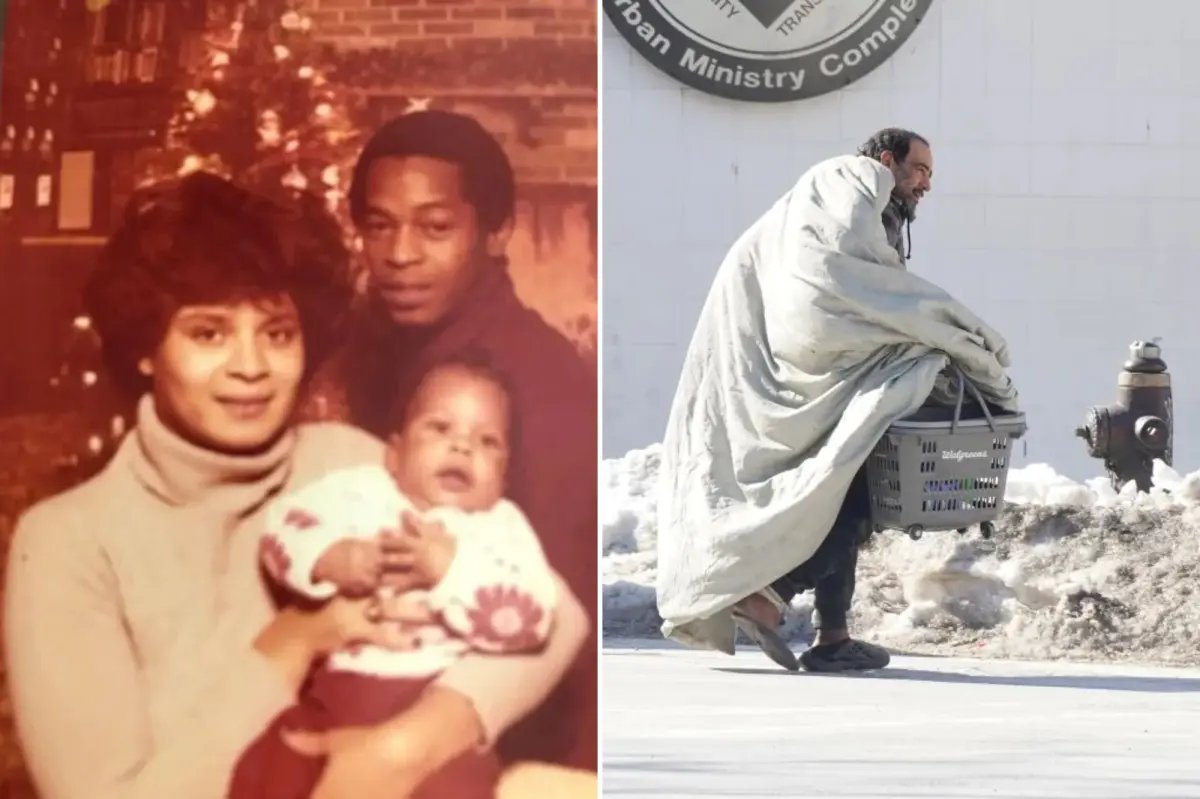

While it is difficult to understand the circumstances surrounding Jones’ death, his beginnings were more clear and stable.

The Queens native grew up in a close family of 13 children, his sister Atkins told The Post.

“Unfortunately, for people with emotional problems or addiction problems, the family can’t do much. All I can say is that the pain of living on the streets was very difficult.” Atkins said.

On Monday, the family held a memorial service attended by a large number of relatives and close childhood friends.

In the service booklet, Jones was remembered for his love for his late mother, Mamie, who “taught him how to drive a Mustang.”

He was described as a “voracious reader” and karate enthusiast who practiced what he learned from watching Bruce Lee on television. He also loved to play the drums and eat seafood at Sunny’s Restaurant on City Island.

He left behind four children and several grandchildren.

In a family statement to The Washington Post, Belcher Ledbetter explained, “He was important to his children, grandchildren, sisters and family who loved him dearly, even when we did not always agree with the choices he made.”

Atkins said her brother “preferred to live on the streets. He didn’t care about shelters because he said they were dangerous.”

She remembered how one of their brothers met Jones on a city street after not seeing him for a while, and tried to give him the coat off his back, but Jones refused.

Despite his instability, Jones regularly worked odd jobs for businesses on Hillside Avenue in Jamaica, Atkins said.

When he moved into permanent housing in Manhattan, Atkins said the family was relieved he had help. But Jones became more isolated, stopped communicating and became essentially disconnected.

“He was always in my prayers,” Atkins said.

McKinley, Jones’ court-appointed conservator since 2023, was shocked to learn he had family nearby. She said that during all of their interactions, he vacillated between clarity and paranoia — but he was always polite and always addressed her as ma’am.

“He opened the door for me and took off his hat in court,” she told me.

When he stopped paying his $246 a month rent — much of which was covered by government programs — in March 2022, Gothamist reported, Breaking Ground sued Jones for nonpayment. This was clearly not to evict him, but to start a legal process that would lead to greater assistance from the city’s Department of Social Services.

Whether insanity, addiction, or both caused Jones to refuse help from his family and others, his housing situation indicates that his basic needs were met.

However, his story highlights how progressive policies like Housing First — which prioritize stable housing without the accompanying conditions of work or sobriety — are not a perfect cure for the difficult and ever-growing problem of homelessness.

“It’s a very popular theory, especially in progressive jurisdictions like New York City: The way you address homelessness is through permanent subsidized housing,” Stephen Eddy, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, told me. “The point is that you have to provide adequate housing and then they can work on solving problems in people’s lives.”

Eddy said advocates tout the success of this approach because people are moving off the streets and into stable homes.

But he said there are two sides to the housing story: One: the part that looks at housing metrics “and the other side that looks at health and mortality. We know that housing is not health care — and bad things can happen if someone just gets housing and the underlying issues are not addressed.”

It’s a twisted form of compassion, as is the city’s reluctance to take people off the streets even when temperatures drop below 32 degrees — known as “code blue.”

“To those who feel most comfortable on the streets, I want to speak directly: I implore you to come inside.” Mamdani said last week As another An oppressive cold wave was descending on the city.

But what about people who can’t think or take care of themselves?

Leaving the decision to get out of the cold in their hands is not humane – and has only led to more tragedy.

The Jones siblings don’t blame the mayor and certainly not the first responders. Although if there’s a lesson from Jones’ death, it’s that sometimes people aren’t the best judges of their own well-being.

“I sincerely hope the city continues to strengthen outreach and support so that other families do not have to experience this type of loss,” Belcher-Ledbetter said.

“If I can offer anything constructive: When the city responds to someone who may be dealing with social-emotional or mental health challenges, my hope is that a trained social worker or outreach worker will be included alongside the police, so that there is a better chance of getting the person to help in the moment.”

While the family still doesn’t have an explanation as to why their brother was out even though he had a place of his own, they do have something that eluded them for years as he battled his demons on the street.

“We have a sense of peace now,” Atkins said.