More than just a feeling – thinking about love as a virtue can change the way we respond to hate

Love and hate seem like obvious opposites. Love, whether romantic or otherwise, involves a feeling of warmth and affection toward others. Hatred involves feelings of contempt. Love builds and hate destroys.

But this description of love and hate treats them as mere emotions. like The world of religious ethicsI am interested in the role that love plays in our moral lives: how and why it can help us to live well together. How would our understanding of the love-hate relationship change if we imagined love not as an emotion but as a virtue?

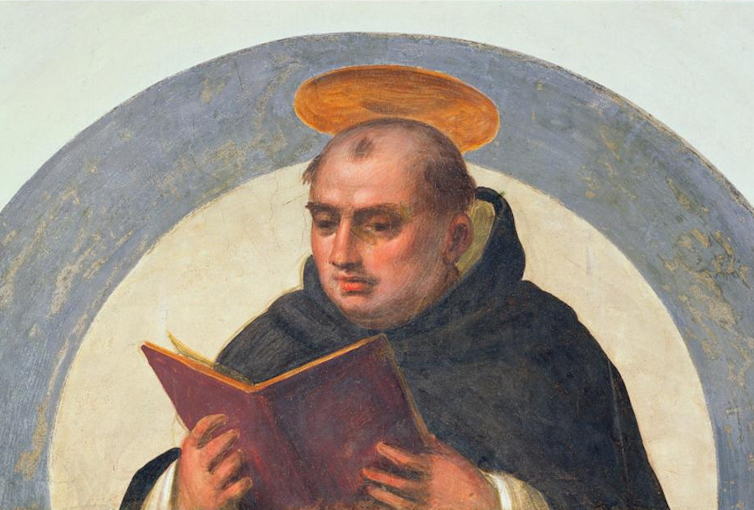

The thirteenth-century theologian Thomas Aquinas is considered a seminal thinker in the history of Christian ethics. For Aquinas, hatred is not the opposite of, or even incompatible with, love. In his most important works,Total theology“Hate responds to love,” he writes. “In other words, hate is a reaction to threats against what we love, or what we deeply value. We can better understand the experience of hate by clarifying what love means.”

Greek roots

Today scientists know this Feelings of love We are Related to biochemical processes Which secretes chemicals in the brain, which increases pleasure and excitement. Beyond just biology or even emotions, some philosophers and psychologists confirm this Love is also a practice.

Love can also refer to a virtue: a stable habit or behavior that increases people’s endurance Thinking, feeling and acting In ways that promote happiness and well-being. For example, the virtue of courage can help people endure and thrive amidst fear and uncertainty.

FatCamera/iStock via Getty Images Plus

The concept of virtue is as old as philosophy itself. in “RepublicWritten in the fourth century B.C., Plato distinguishes between virtue in general and individual virtues that he believed characterize well-being, such as wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice.

Love is not between them. Instead, he links love – for which he uses the Greek word “eros” – With feelings of physical desire.

It was Aristotle, one of Plato’s students, who made love closer to virtue. According to AristotleNicomachean ethics“Virtue, he writes, involves learning how to act and feel ‘at the right times, toward the right things, toward the right people, to the right end, and in the right way.’” Individual virtues are developed over time through repetition.

For an action to be virtuous, one must act consciously and deliberately for some moral value. For example, Aristotle says that a generous person does good By giving wealth to the right people. A person who spends with the aim of obtaining some benefit in return only appears generous. A person’s character and the spirit in which he presents are important.

A virtuous life isn’t easy – but true friends can help. Aristotle believed that relationships of mutual respect and caring could enable us to develop virtues. Unlike circumstantial or superficial friendships, These deeper connections are characterized by “philia.”“, a kind of love. Friendships based on love are virtuous: they involve mutual accountability and care for each other, as if each person were an extension of themselves.

Take Aquinas

The Christian moral tradition builds and expands on these Greek foundations. For Christian theologians and moral philosophers, love can refer to an affection, a passion, a duty, and yes, a virtue.

Aquinas regards virtue as the stable disposition of the will – our ability to choose – it Contributes to a good life. Individual virtues are good habits that influence how we treat ourselves and others in our daily lives, including love.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

He also views love as a theological virtue – a gift of God’s grace that people can choose to accept or reject. Caritas, or “love” in Latin, is defined as friendship with God. Aquinas writes that it has a social benefit as well: caritas moves people toward treating their fellow human beings kindly, and working to promote the well-being of others.

The other types of love, eros and philia, are subjective. They respond to our perception of value in other people and things. Caritas creates value in others, whether we are able to see it or not.

Love and hate

How can treating love as a virtue—rather than as an emotion, an emotion, or a biochemical reaction—help us understand the feelings of hate?

In Aquinas’ view, the feeling of hatred depends on the people and things we like, or consider good for ourselves and others, whether that is a sports team, a movie, or an ideology.

However, if we view love as a virtue—a daily habit that we choose to guide our practices—we can exercise a degree of control over how we respond to feelings of hate.

Think about how much hatred there is in politics, such as hatred of a particular policy, politician, or belief – or hatred of injustice itself. But fundamentally, perhaps this hatred is a response to love; For example, love of one’s neighbors, one’s country, or one’s ideals. Recognizing this possibility can help us respond with a loving choice, such as peaceful protest, as a way to stand up for rights. By cultivating the virtue of love, people become more likely to engage in the caring and compassionate practices necessary for communities to flourish.

Distinguishing between feelings of love, practices of love, and the virtue of love can enable us to respond to feelings of hate. Becoming better lovers requires dealing with destructive feelings, rather than running from them.