Green or not, the future of energy in the United States depends on the countries of origin

The Trump administration’s campaign Increase domestic production of fossil fuels and Mining of major minerals It probably couldn’t be done without a key audience: indigenous peoples.

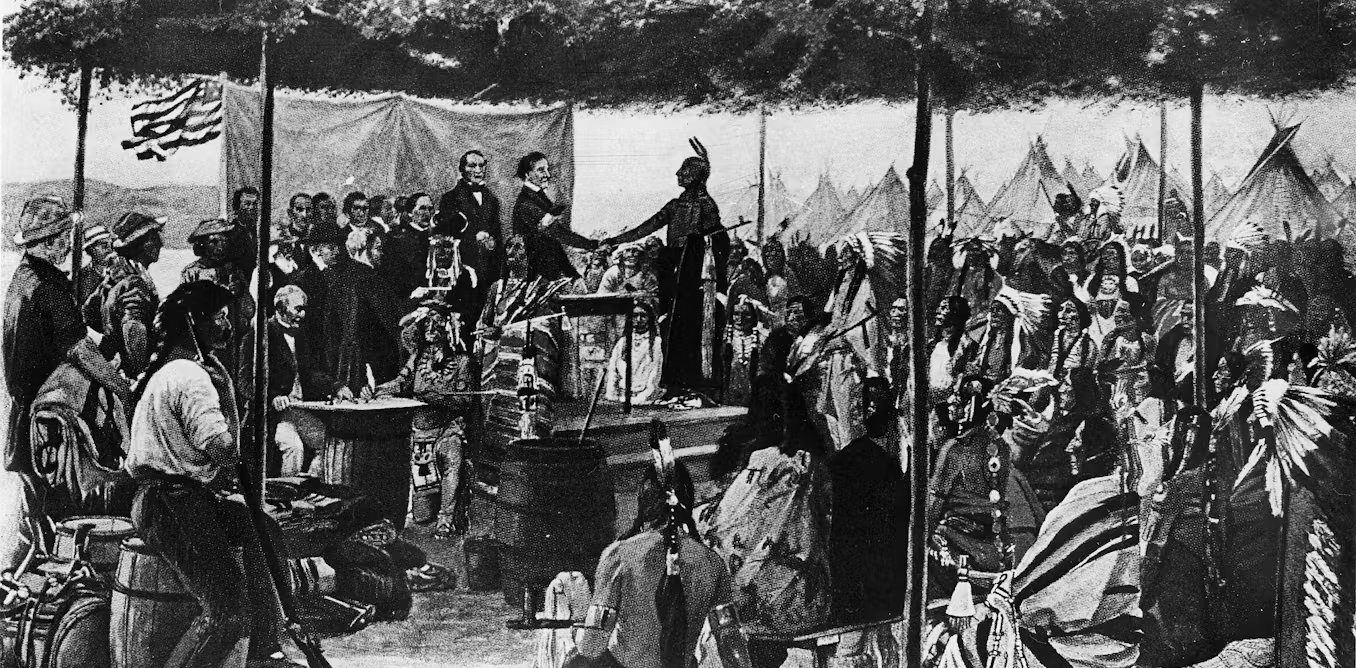

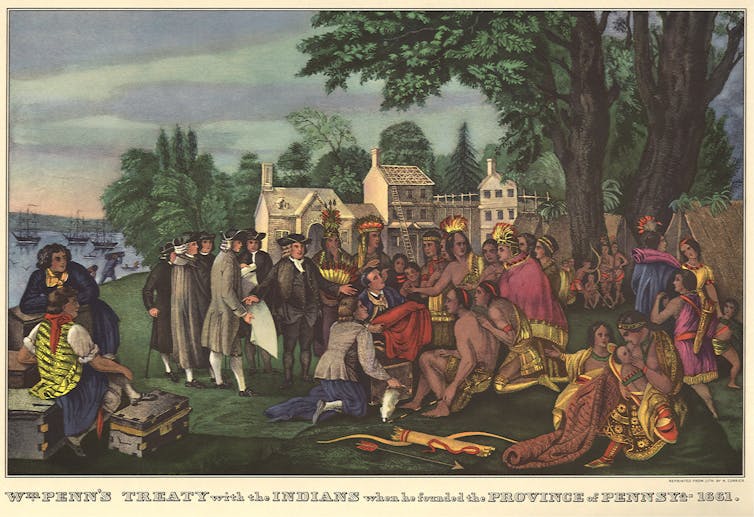

The United States has 374 treaties with 574 Governments of sovereign states Within the borders of the United States, governance 2.5% of the state’s landsmostly west of the Mississippi River.

Contains Native American tribal lands 30% of the coal the country produces, 50% of uranium, and 20% of natural gas.. They contain materials critical to advanced technologies, including renewable energy: copper for power grids, lithium and rare earth elements for batteries and electronics, and water for agriculture and power generation.

Significantly expanding domestic access to fossil fuels, critical minerals, and water will require the U.S. government to work with indigenous peoples. Their rights to the resources on their lands are stipulated in long-term treaties Equal legal authority The American Constitution itself. I study these agreementsIt was negotiated from the late 18th to the late 19th century and ratified by the US Senate. They are not just historical artifacts, they are key documents at the heart of modern conflicts over drilling, mining, pipelines and energy infrastructure.

For indigenous nations, access to natural resources is more than just a matter of economic opportunity or environmental sustainability. The administration of these lands cannot be separated from questions of sovereignty, sacred lands and treaty enforcement.

Treaties as living law

Under the United States Constitution, treaties are classified as “The supreme law of the land“Besides the Constitution itself.

The Federal Indian Act, largely codified in Title 25 of the United States Codedefines the relationship between the United States and tribal nations, including recognition of tribes as possessing and practicing “autonomySupreme Court decisions sometimes recognize tribes Sovereign political entitiesBut this Sovereignty is restricted By the authority of Congress and the overlapping jurisdiction of the State.

These treaties have long been viewed as tools that allowed settlers of European origin to exist Annexation of original lands. But they are too Permitted activity On land the tribes never formally surrendered. One treaty with the Eastern Shoshone allowedMining settlements“On lands allocated to one tribe while another allowed.”“Exploration” for “minerals and minerals”.“.

But in recent decades, indigenous nations have used the treaties as a basis for reasserting their sovereign status, returning the documents to their original purpose as an organized set of nation-to-nation relationships deeply rooted in history. Diplomatic History of North America.

particularly, Indigenous activism and litigation Since the 1970s, treaty claims have been revived as tools to protect lands, waters and cultural practices. Treaties that have been dismissed as instruments of expropriation are increasingly cited as Binding legal obligations – In proportion to, and capable of, Formulating contemporary energy policy.

AP Photo/Steve Karnovsky

Energy projects and treaty disputes

The tribes are demanding the federal government for protection Holy Land, Ecosystems and Community health When evaluating proposals for mining and other developments.

Indigenous-led protests and lawsuits are a common feature of large infrastructure projects that cross their lands or threaten their resources. In 2021, White Earth Nation He sought to prevent expansion Enbridge oil pipeline 3. The road is planned to run under the spiritually important Minnesota Lake where it and other tribes have treaty-protected water, hunting and fishing rights.

In his effort that was Ultimately unsuccessfulthe The tribe cited treaties From 1837, 1854 and 1855. The tribe claimed that these treaties required the federal government to protect their rights to hunt, fish, and gather—a position they supported 1999 Supreme Court ruling.

More successful was the move by the Navajo Nation in 2024 to obtain the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission The proposed hydroelectric project was rejected On Navajo lands.

However, in late January 2026, the committee approved A A similar hydroelectric project in an area that is sacred and protected by treaty From the lands of the Yakama Nation in Washington State. The Yakama and other native tribes and groups are asking state courts to block the project.

These cases reveal a Long-term stress In United States law between the federal government’s treaty-related responsibility to protect tribal resources and the authority claimed by the federal and state governments over lands and development.

AP Photo/Ty O’Neill

Oak Flat and Apache Stronghold status

One of the most important current disputes involves the proposal Copper resolution Mine in Oak Flat, Arizona. Oak Flat is known to the Western Apache as Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, a sacred site used for ceremonies Central to Apache religious life.

In 2014, Congress authorized the transfer of approximately 2,422 acres of federally protected lands in Tonto National Forest For mining company through Southeastern Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Actan integral part of the defense spending bill. If permitted, the proposed underground mining on that land constitutes a Risk of decline and possible collapse From the site.

In 2021, the Apache-led coalition of Apache strongholds filed a lawsuit against the US government, arguing that the transfer of land ownership Violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act And the provisions in 1852 Treaty of Santa Fe Which requires the government to respect tribal lands.

The courts have so far sided with the federal government on the basis that Congress, not the states, has the final authority over so-called federal law.”Indian country“.

First, a US District Court denied an injunction to stop the transfer. In March 2024, judges for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a split ruling upholding this decision and finding that The project did not impose a “significant burden.” Concerning the religious rights of the Apaches.

In May 2025, the US Supreme Court He refused to hear the case. However, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas wrote that they wanted to hear the case. They warned that by not listening to her, the court would Allowing the destruction of a sacred religious site.

The Apaches tried again in late 2025, but the Supreme Court This request was also rejectedleaving intact the Ninth Circuit ruling, which allowed the land to be transferred to the mining company.

However, the struggle is not over yet. Apache took additional claims to the Ninth Circuit in A Different legal formthe court issued Temporary restraining orders in late 2025, pausing aspects of the land transfer as litigation continues.

Picturenow/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Why are treaties still important?

The Oak Flat dispute highlights the limits of current legal protections for Indigenous sacred sites, even when treaties and religious freedom are clearly at stake. It also shows how Congressional control over the use of federal lands can override indigenous objections in the name of energy security and critical minerals.

This and similar disputes also show how treaties, federal law, and the Constitution can be used to slow, reshape, and sometimes stop extractive projects, forcing states and corporations to reckon with indigenous sovereignty, even when Congress or the executive branch has the final say.

For indigenous nations, treaties remain central tools for asserting sovereignty and shaping energy futures. Tribal governments and indigenous companies are increasingly active in, and seeking development in, renewable energy and minerals markets Their own terms. In April 2025, Poe Negrin, chief of the coal-rich Navajo tribe, called for energy development Respect tribal sovereignty And securing the position of home countries in global supply chains.

Treaties are not a relic of the past. They continue to shape how energy, law, and sovereignty intersect in the United States today.